From paper trails to digital paths: Rippling’s journey to the Documents Engine part 2

![[Blog – Hero Image] Run on Rippling](http://images.ctfassets.net/k0itp0ir7ty4/1ganvmImeTEU5ydLcM0y33/ad3d631b7d7e6138b67ef020393d762f/Run_on_Rippling_-_Spot.png)

In this article

Recap

Part 1 covered how Rippling's Filings Engine and its core Document Engine are crucial for managing payroll and tax obligations across various agencies. The system generates over 10 million documents weekly, ensuring compliance with diverse agency requirements, which vary from electronic (XML, Fixed-Width, CSV/TSV) to paper-friendly (PDF) formats. In this post, we continue by describing how we operate this system efficiently at a large scale.

Generation at scale

Once the challenge of gathering accurate data for our documents is resolved, the next problem is to generate them on a large scale in an efficient way.

There are a few key scalability factors we leverage:

Within a single process (Go)

The Cloud (Kubernetes)

Task orchestrator (Temporal.io)

The database (Aurora RDS Postgres)

Maximizing throughput within a single process

Most of our project is built in Go, a language known for its exceptional built-in support for concurrency. When dealing with scenarios involving the processing of large volumes of data that are not interdependent, it is advisable to architect the system with concurrency at the forefront. While concurrency in Go is a broad topic, we will demonstrate at least one sample of how it can be used at the code level.

In our specific scenario, we have two examples of leveraging concurrent processing: (1) creating a single document that needs to contain data on each of our expanding pool of thousands of clients/customers, and (2) creating individual documents for each client/customer.

The bulk document case, containing data for multiple clients, can leverage Go concurrency. Imagine running a single process where you want to maximize the throughput. If we assume that there’s a generateClientsData(clientId) method that is concurrency-safe and non-blocking, we can parallelize it using goroutines. Let’s illustrate this using a ResultPool from the "github.com/sourcegraph/conc/pool" package; although this can be implemented with a plain old go channel, using conc helps with code readability:

This would start up to BulkParallelism goroutines that allow us to process each generateClientData call independently, without the need to manually manage the concurrent processes or think about threads.

There are a few caveats that could have their own blog posts, but at least let’s highlight them for consideration:

The optimal number of concurrent goroutines varies depending on the specific use case. For CPU-intensive tasks, a recommended starting point would be to utilize the result of

runtime.GOMAXPROCS, which corresponds to the number of CPU cores available on the system. However, if your workload is predominantly I/O-bound, most goroutines would remain idle, allowing for consideration for a higher count. It is crucial to also factor in the weakest component in the chain of interconnected services. For instance, setting a sensible limit becomes essential to avoid putting too much load on a shared database.The order of output in this use case is non-deterministic. If you care about preserving the input order, the return value can be, for example, converted to a struct that contains both the value and the index that it should be inserted at.

This approach helps utilize the CPU resources to the maximum for a bulk file with a significant amount of independent items, but doesn’t provide any solution for scaling it up to tens of thousands of files in parallel. This is where a single machine is not enough.

Scaling in Kubernetes

Rippling uses Kubernetes to run all of our applications, and the tech has proven itself useful here as well. With Kubernetes, a single application’s deployment can span across multiple pods — each pod is an independent instance (with one or more containers).

Let’s say the job of generating documents is executed by a document-generation worker. Deploying multiple pods of this worker can enhance the system's throughput. There are several variables to optimize for here:

Cost: More pods mean more nodes needed to host them, meaning higher cost

Divisibility of tasks: Depending on the specific use case, there comes a juncture where further division of work becomes impractical or unfeasible. This imposes a limit on the number of workers that can effectively share the workload.

Downstream dependencies: The workers may need to communicate with external services, such as a database, to perform their tasks. Setting the pod count to be too high can put an excessive load on the DB, leading to potential performance issues, increased response times, or even service outages. It's essential to balance the pod count to ensure efficient resource utilization without overwhelming external services. The downstream services may be scalable at a higher cost, making it more feasible to limit the scale instead.

Shared state: Separate pods mean separate states, which makes data structures like shared in-memory caches less efficient. For example, we can no longer pre-load data for all the jobs in one query. The introduction of a shared cache across pods would be a further trade-off — it complicates the architecture, so in certain cases, splitting the work into less granular chunks may turn out to be more optimal.

Let's start by discussing cost efficiency. One way we tackle this challenge is through autoscaling. Instead of maintaining the maximum number of worker pods constantly active, we adapt to the fluctuating nature of our workloads. Typically, our workloads experience bursts of activity, resulting in periods where the extra machines are unnecessary. By scaling down during these times, we can reduce infrastructure costs. On the other hand, when a surge of work occurs sporadically, we scale up temporarily to accommodate the increased demand.

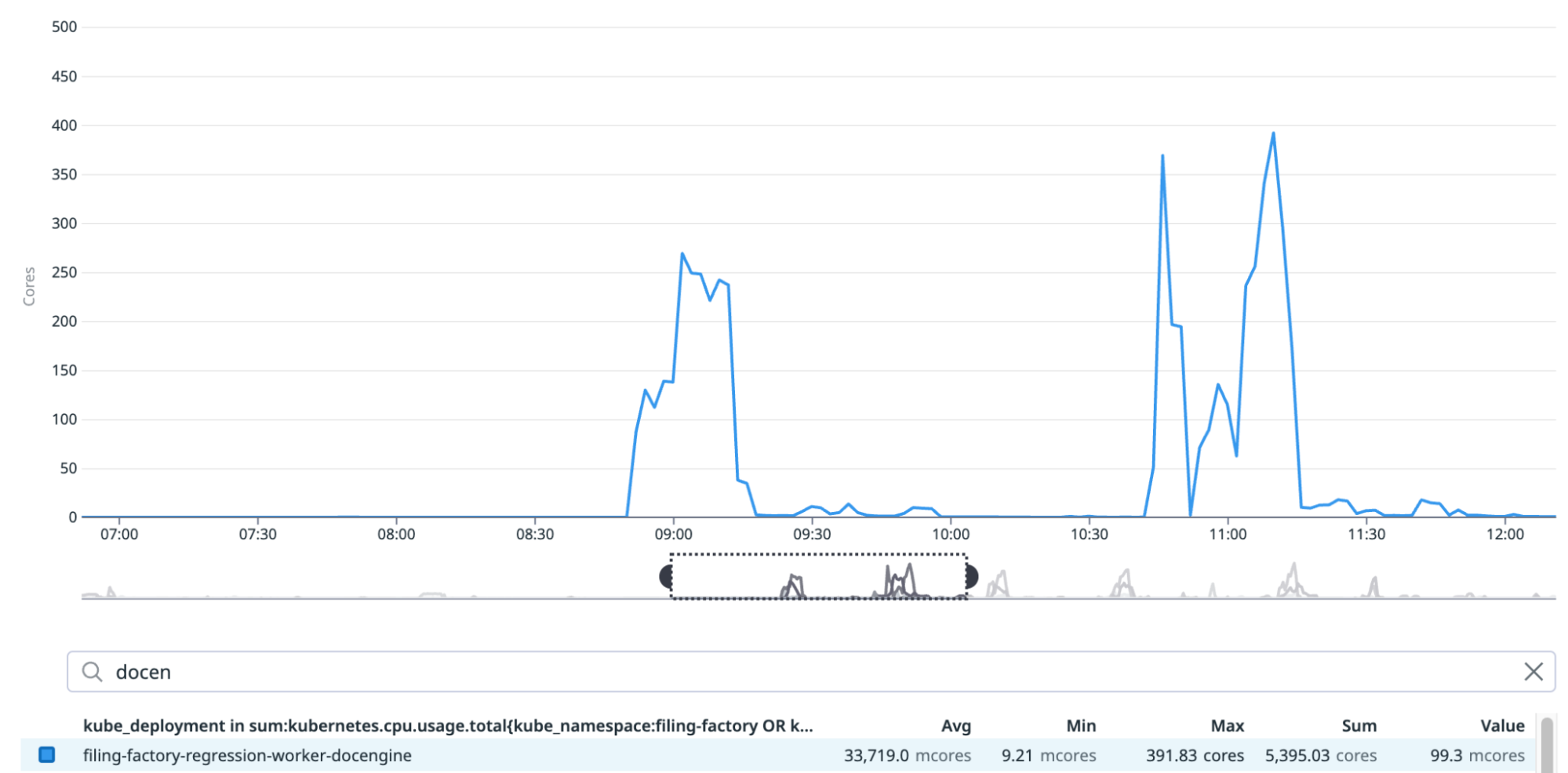

To better understand the spikes, examining the total CPU usage metric is crucial. In our case, this value can vary significantly, ranging from less than 10 milli-cores (meaning 1% of a single CPU core) up to a peak of around 400 CPU cores. Moreover, the usage can steeply rise within a small number of minutes as more documents are added to the queue. The following plot shows a typical pattern for this metric over a 5-hour time window:

The most basic approach to autoscaling, which usually brings “good enough” results at a low effort, is CPU-based autoscaling. In Kubernetes, you can define an additional resource in your cluster, a HorizontalPodAutoscaler, that will control the replica count of your deployment based on a metric.

Many examples that work for standard loads (e.g., an app serving HTTP requests) will by default suggest using a 50% CPU usage target to do the scaling:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

apiVersion: autoscaling/v2

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: document-generation-worker-hpa

namespace: your-namespace

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: document-generation-worker

minReplicas: 1

maxReplicas: 100

metrics:

- type: Resource

resource:

name: cpu

target:

type: Utilization

averageUtilization: 50This would aim to reach an average CPU utilization of 50% across all the pods. If the CPUs are utilized more than 50% on average, it will add more pods (scale up); if less than 50%, it will destroy them (scale down).

However, we know our load is bursty, and if there’s any work, there’s probably a lot of it. This means it also works for us if we set a much lower CPU target, say 20%, and a faster scaling policy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

behavior:

scaleDown:

stabilizationWindowSeconds: 300

policies:

- type: Percent

value: 50

periodSeconds: 15

scaleUp:

stabilizationWindowSeconds: 0

policies:

- type: Pods

value: 4

periodSeconds: 15

selectPolicy: MaxThis configuration allows for quick scaling up (adding up to 4 pods every 15 seconds) to handle sudden increases in load, while being more conservative when scaling down (waiting for 5 minutes and then reducing by up to 50% every 15 seconds). This approach helps us quickly respond to increased demand while avoiding premature scale-downs that might lead to performance issues.

Note that there’s no delay in scaling up (stabilization window 0 seconds), but the HPA will wait for 5 minutes (300 seconds) before considering another scale-down action.

Is there a more suitable measure to base our scaling on? Yes, there is! The demand on these pods in our system is not primarily determined by direct RPC requests, but rather by the task queue. This approach enables the distribution of load spikes over time, eliminating the need to respond immediately at all times.

Ideally, the number of pods to spin up should be determined by a metric that indicates the amount of queued work. Whether such a number is directly available depends on your queue and metrics system, which leads us to the next question: how do we orchestrate the work?

Workflows and tasks — the Temporal framework

To manage the document generation at scale, we use Temporal as the framework for task orchestration. Its main units of flow control are workflows and activities. A workflow is a piece of code that only defines the control flow and should never run any compute-heavy or I/O operations directly. It can, however, call one or more activities, which represent the actual atomic operations, and serve as building blocks for the workflow. Both workflows and activities have well-defined inputs and outputs.

Workers sign up for a specific Temporal queue, where each worker listening to this queue should be capable of handling any of its scheduled workflows or activities. Temporal Cloud manages the queues in our setup, but you could run it entirely within your infrastructure as well. The workers are always running inside our Kubernetes cluster, and are programming language-independent. As of July 2024, Temporal provides SDKs for Golang, Python, Java, PHP, TypeScript, and .NET. A child workflow can run in a different queue than the parent. This allows you to leverage a different programming language for certain tasks by setting up a distinct queue and assigning workers specifically for that segment of work. These workers will then handle tasks and send the results back to the parent workflow, across the different tech stack boundaries.

Temporal also emits metrics, which gives us another good source for autoscaling. In multiple workers, we scale up on a rising value of activity_schedule_to_start_latency — signifying how much time has passed between an activity being scheduled for execution, and picked up to be processed. The more waiting time, the busier the system is, since there are not enough workers to pick up new jobs immediately.

PDF generation details

Generating CSV and text files is a straightforward task, and XML is not far behind in ease of use. However, Portable Document Format (PDF) files are more complex. Introduced in 1993 and open since 2008, PDFs are often perceived as binary files due to their complexity and the ability to embed various elements such as images and fonts. While PDFs are internally organized using ASCII-based commands, managing them at a low level for each project that requires PDF generation is too complex. Therefore, we decided to find an external library to handle the format-specific operations.

When generating tax forms, we leverage a feature of PDFs that you may be familiar with as a user — support for fillable forms, with well-defined form fields (text fields, check boxes, and alike). Such forms are defined inside the PDF file itself, and we looked for a good, open, and easy-to-use library that would understand such annotations and let us inspect and fill out a form. We ultimately chose pdf-lib by Andrew Dillon, published under an MIT license.

It’s a TypeScript library, so instead of incorporating it into the binaries that handle our document generation workflows, we delegate the PDF-specific tasks to a separate microservice. It’s built to be stateless and has no external dependencies. All the data it needs for each request is expected to come in the request payload, and the result of the file operations is fully returned in the response.

This separation allowed us to use a different setup for autoscaling on the PDF end — since PDF operations come in bursts, and are usually very quick, after which the CPU becomes idle, we can autoscale based on CPU here very well — with a policy to scale up fast, and scale down much slower, with lower decrements.

Autoscaling the DB

One last part of the infrastructure that we decided to scale dynamically is the database. We use Amazon’s Relational Database Service (RDS), set up with Terraform. Usually, you specify a number of RDS instances, and for each instance, you specify a machine size. The machine size determines the number of CPUs and gigabytes of RAM you are getting, which very well translates to performance in the case of the Postgres database.

However, Amazon also provides a special instance type, called “Serverless v2” as part of AWS Aurora. Here we can specify the DB's minimal and maximal capacity in… well, capacity units (ACU — Aurora Capacity Units). One ACU gives us roughly 2 GiB of RAM. If our instance is supposed to scale from 1 to 32 units, it would get from 2 to 64 GiB of RAM. This gives us a DB that can scale vertically, on demand, and most importantly, without interruption of any of the operations. It’s important to remember that a “serverless” instance is still a single instance — for horizontal scaling, more instances can still be defined and utilized.

The factor to consider here is cost — our experience says it can get anywhere from 4x cheaper than the regular database instance (when idle) to 4x more expensive (when scaled up to the same size). For bursty sporadic workloads, like ours, it’s almost half the cost on average.

What’s next

Rippling’s document engine has allowed us to successfully process more than 900M documents for tens of thousands of customer companies. While our focus here has been on the generation side, the system also handles documents received from agencies, e.g. agency notices and power of attorney. For this process, the team is investigating GPT models to parse the submissions and extract valuable insights back into the system.

Disclaimer

Rippling and its affiliates do not provide tax, accounting, or legal advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide or be relied on for tax, accounting, or legal advice. You should consult your own tax, accounting, and legal advisors before engaging in any related activities or transactions.

Author

Cezar Pokorski

Staff Software Engineer

Software Engineer passionate about elegant solutions, with 2+ years in Golang, 5+ in Python, even more with JS/TS, and a lifelong love for coding (and 8-bits) since his first 10 PRINT"Hello world": GOTO 10.

See Rippling in action

Increase savings, automate busy work, and make better decisions by managing HR, IT, and Finance in one place.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33import ( "context" "fmt" "strings" "github.com/sourcegraph/conc/pool" ) const BulkParallelism = 8 func generateBulkDocuments(ctx context.Context, clientIDs []string) (string, error) { runnerPool := pool.NewWithResults[string](). WithContext(ctx). WithMaxGoroutines(BulkParallelism). WithCancelOnError() for _, clientID := range clientIDs { runnerPool.Go(func(_ context.Context) (string, error) { csvLine, err := generateClientData(clientID) if err != nil { return "", fmt.Errorf("error generating data for client %s: %w", clientID, err) } return csvLine, nil }) } // Wait for all tasks to complete and collect results csvLines, err := runnerPool.Wait() if err != nil { return "", fmt.Errorf("error in bulk document generation: %w", err) } return strings.Join(csvLines, "\n"), nil }